The air still smelled like crushed mint and damp compost when I rolled up my sleeves at Grow Maryland Farm last spring. Owner Lena Chen wasn’t just showing me their prize-winning heirloom tomatoes-she was demonstrating how their hydroponic basil had reduced water usage by 40% while doubling yield. That’s the Maryland horticulture economy in action: where science meets soil, and every penny spent on irrigation directly funds the next generation of local farmers. The state’s $1.76 billion industry isn’t just about pretty bouquets or sprawling vineyards. It’s about resilient communities, hidden innovations, and the quiet heroism of workers who keep the fields turning.

Maryland horticulture economy: Where the money really grows

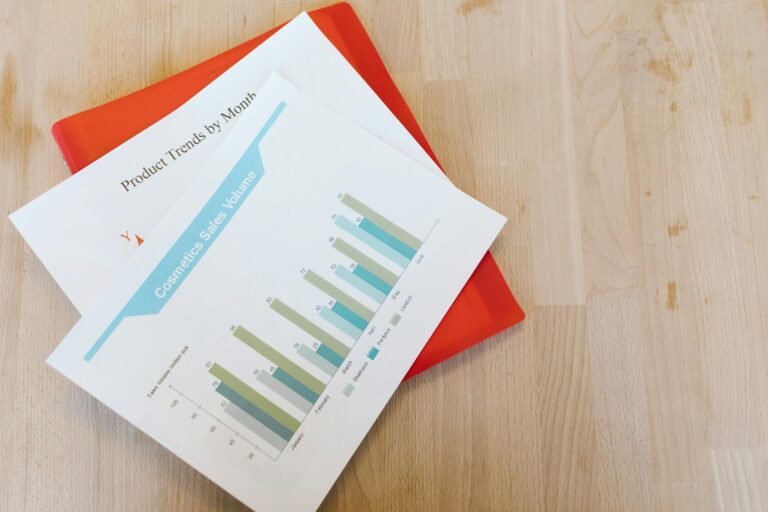

Floriculture steals the spotlight-Maryland supplies nearly half the nation’s chrysanthemums and a third of its poinsettias-but the $1.76 billion figure includes far more than holiday cut flowers. Nursery crops alone generate $800 million annually, from the shade trees lining Baltimore’s streets to the bedding plants that fill suburban mailboxes in spring. Then there’s the vegetable sector, where Terrapin Farm Company in Queen Anne’s County proves organic isn’t just a trend-it’s a $120 million business model. Their heirloom tomatoes sell for premium prices at farmers’ markets while teaching farmers how to cut pesticide use by 60% without sacrificing yield. The industry’s success? It’s not about growing more-it’s about growing smarter.

Behind every $1.76 billion statistic is a workforce that often goes unnoticed. Maryland’s horticulture economy supports over 45,000 jobs, from the migrant workers harvesting strawberries at sunrise to the certified agronomists calibrating soil pH with GPS precision. The challenge? Retaining talent. I visited Harvesters Community Farm in Prince George’s County, where they solved this by turning labor into a career pipeline. Their green-thumb apprenticeship program-partnered with local high schools-now trains 80+ students yearly in everything from compost science to micro-business startup grants. One graduate, Jamal, now runs his own urban farm in Capitol Hill, selling direct-to-consumer while teaching weekends classes. That’s the Maryland horticulture economy’s secret sauce: it’s not just about the harvest-it’s about the harvesters.

Who’s really driving the industry

The $1.76 billion number gets a lot of attention, but the real drivers are the players most people never see:

– Small-scale diversifiers: Farms like The Growing Place in Harford County, which started as a $20K startup and now ships $1.2M worth of microgreens to Washington DC restaurants.

– Corporate innovators: Honeygo Round Greenhouses blends 50-year-old rose varieties with vertical LED farming, extending their season by 3 months without pesticides.

– Urban pioneers: Baltimore’s Back to the Land Co-op turns vacant lots into high-yield plots, supplying 10,000+ meals annually to food deserts.

Yet even these success stories face the same hurdle: access. 40% of Maryland’s growers struggle with land costs or market connectivity. The industry’s future depends on fixing that-but the solutions aren’t flashy. Shared cold storage hubs in rural areas. Direct-to-consumer platforms that bypass middlemen. Grants for high-tunnels that let farmers extend seasons. Maryland’s horticulture economy isn’t about waiting for change-it’s about building the tools to make it happen.

Innovation that actually works

Innovation in the Maryland horticulture economy doesn’t look like Silicon Valley. It’s a farmer in Frederick County using rainwater harvesting to cut costs by 25%. It’s a Prince George’s County greenhouse replacing soil entirely with aeroponics, slashing fungal diseases by 80%. And it’s a Prince George’s County greenhouse replacing soil entirely with aeroponics, slashing fungal diseases by 80%. The key? Practical, low-tech solutions that adapt to Maryland’s climate challenges.

Take climate-smart agriculture. The state’s carbon-sequestering cover crops (like winter rye) are now a $5M annual market, with farmers earning $80/acre in carbon credits. Meanwhile, precision agriculture-using drones to monitor irrigation-has helped Western Maryland apple growers reduce water use by 35% while increasing yield. Even urban farms are leading the way: DC’s Farm-to-School Program connects 300+ schools to local producers, teaching kids how their meals grow while cutting food miles by 90%.

But here’s the catch: innovation alone won’t save the industry. Maryland’s horticulture economy needs policy to match its grit. For example, shared infrastructure (like a $3M state-funded cold storage hub in Salisbury) could help smaller farms compete-but it requires consistent funding. Similarly, training programs (like the $1.5M USDA grant for sustainable agriculture education) need long-term support. The state has the potential to redefine regional agriculture-but only if it treats the people behind the plants with the same care as the plants themselves.

The $1.76 billion Maryland horticulture economy isn’t just a number-it’s a living system, where every pruned leaf and every new variety planted is part of a bigger story. I’ve watched Lena Chen at Grow Maryland argue with her soil samples, Jamal at Harvesters negotiate his first equipment lease, and a Frederick County rose grower test a climate-resistant hybrid that might save his operation when temperatures rise. These aren’t just farmers. They’re problem-solvers, educators, and economic multipliers-each with their own version of the industry’s mantra: grow now, plan for tomorrow.

The next chapter? It’s already being written. Whether it’s lavender fields on the Eastern Shore, heirloom apple orchards in Western Maryland, or a new generation of urban growers in Baltimore, the Maryland horticulture economy will keep thriving-not because it’s the biggest, but because it’s the most adaptable. And that’s a bloom worth watching.